Double Diamond Exercise

About

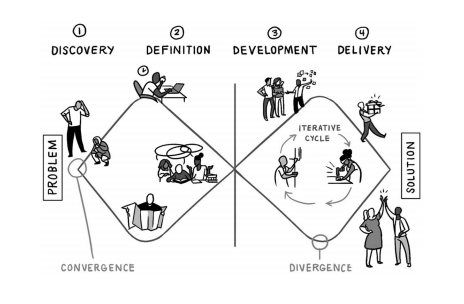

This model begins at a point of convergence at a particular problem and diverges as the team explores the problem from all different angles (often referred to as the Discovery phase). From this broad exploration, the team then works toward convergence in Definition, the second phase. This means they define a specific area of focus, bearing in mind the unique aspects of their problem, audience, and context. At this point, they often write a specific definition for their problem. The next phase, Development, is a second opportunity for divergence; it is here that the team generates as many different design concepts as possible in response to their problem definition [1 -p. 145].

- Discover – The first diamond helps people understand, rather than simply assume, what the problem is. It involves speaking to and spending time with people who are affected by the issues [1 – p. 145].

- Define – The insight gathered from the discovery phase can help you to define the challenge in a different way [1 – p. 145].

- Develop – The second diamond encourages people to give different answers to the clearly defined problem, seeking inspiration from elsewhere and co-designing with a range of different people [1 – p. 145].

- Deliver – Delivery involves testing out different solutions at small-scale, rejecting those that will not work and improving the ones that will [1 – p. 145].

Our Iteration of the Double Diamond Exercise

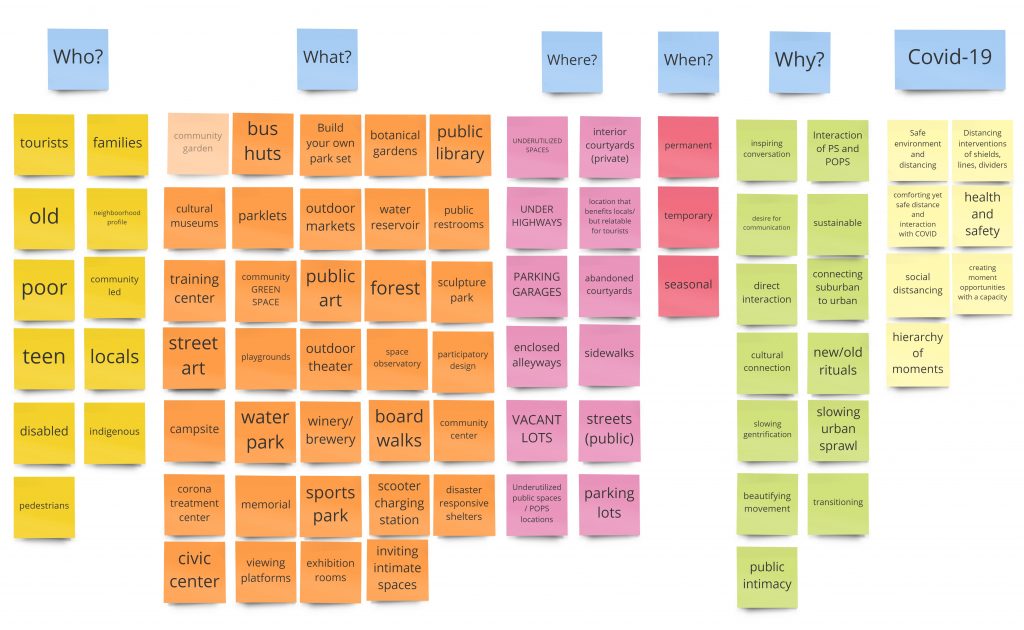

In preparation for devising our competition proposal, we divided up important topics of consideration into the “who, what, where, when, and why” and included Covid-19 as well. Within each category, we listed topics that may be of interest to further research, each topic of course relating to the city of Queretaro. The “who” pinpoints a specific audience in which we wish to cater our urban design towards: tourists, families, old, poor, teens, locals, pedestrians, indigenous, communities, disabled, etc. The “What” explains design ideas and concepts that we may implement: bus huts, outdoor markets, public art, civic centers, cultural museums, public libraries, board walks, sport parks, etc. The “Where” determine a destination in need of our urban design plan: underutilized spaces, vacant lots, under highways, alleyways, public streets, interior private courtyards, etc. The “When” sets a duration for the project proposal: permanent, temporary, or seasonal. The “Why” states the reason behind initiating an urban design plan in the first place: to beautify, for public intimacy, to slow the urban sprawl, to interact with underutilized spaces, for sustainable living, etc. Lastly, “Covid-19” becomes incorporated into the design proposal by: creating social distancing, providing health and safety, etc.

Who, What, Where, When, Why + Covid-19

Focus Quest

About

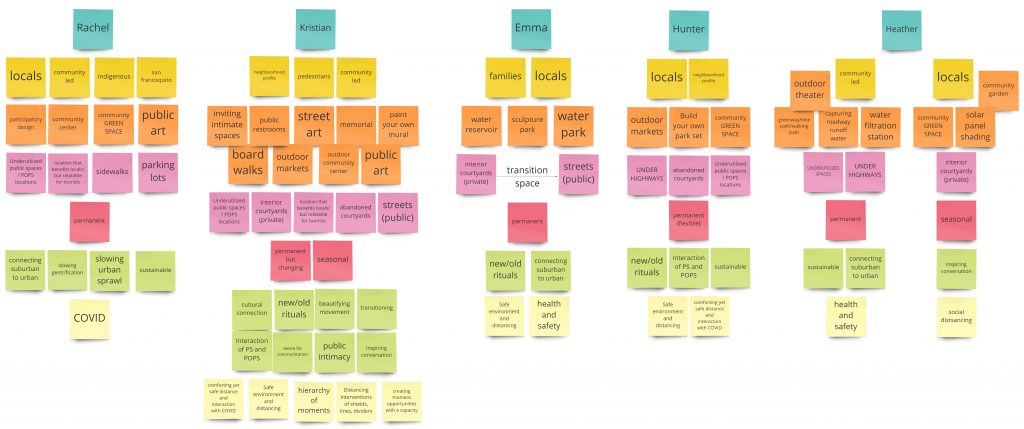

After piecing together our version of the Double Diamond Exercise, we next participated in the Focus Quest exercise. Each teammate worked independent in creating their own version of a competition proposal. We each took sticky notes from the charts above to formulate a plot and solution – covering the “who, what, where, when, why and covid-19” subjects. The Focus Quest activity guides teammates in determining a rallying point that they can discuss together [2 – p. 147].

The ultimate goal of the Focus Quest is to determine a shared topic or focus for the remote team to further explore or work on together. Brainstorming, mapping, and collaging encourage idea generation and moments for collaborative exchange and dialogue. In the end, bringing these ideas together into a collaborative collage encourages teammates to find and observe harmonious combinations of interests and to literally see what others are thinking [3 – p. 148].

5 Individual Proposals

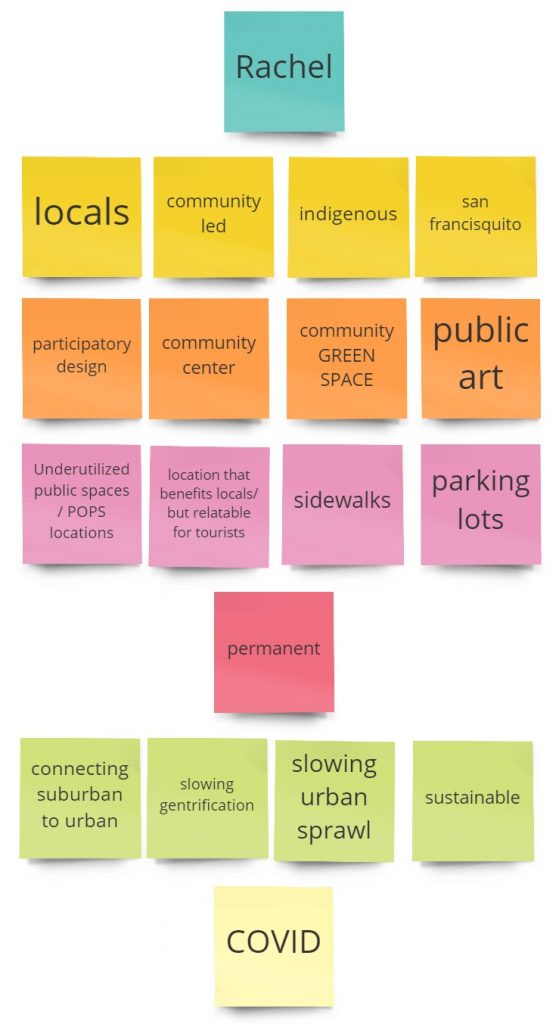

Rachel’s Proposal

- Who: locals, community, indigenous people

- What: Participatory design, community centers, green spaces, and public art

- Where: Underutilized Public Spaces and POPS locations, areas that benefit the locals and tourists, sidewalks, parking lots

- When: Permanent

- Why: Slow urban sprawl and gentrification, connect suburban to urban areas

- Pandemic: Public response to global pandemic

Kristian’s Proposal

- Who: Neighborhood profile, pedestrians, community

- What: Inviting intimate spaces, public restrooms, street art, memorials, mural paintings, board walks, outdoor markets, outdoor community centers, public art

- Where: Underutilized Public Spaces and POPS locations, interior private courtyards, areas that benefit the locals and tourists, abandoned courtyards, public streets

- When: permanent, seasonal but changing

- Why: create a cultural connection, included new/old rituals, beautify, provide a transition space, make use of Public Spaces and POPS spaces, create public intimacy, inspire conversation

- Pandemic: safe comfortable distance, safe environment, distancing interventions like shields, lines, and dividers

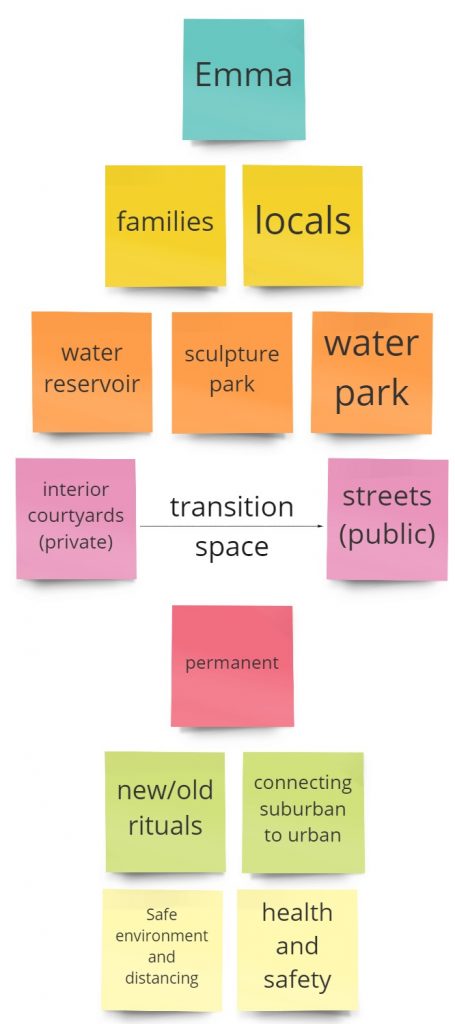

Emma’s Proposal

- Who: families, locals

- What: private water sculptures, water irrigation systems, water filtrations and storage, public water parks, drinking stations, public restrooms

- Where: interior private courtyards, ally transitioning space, to public streets

- When: Permanent

- Why: Resolve water shortage issues, provide space for public interaction, relate to new and old rituals, connect suburban to urban, not disrupt current public culture and norms, create both a literal and hypothetical “flow” between people and the community

- Pandemic: safe environment and social distancing

Hunter’s Proposal

- Who: locals, neighborhood profile

- What: outdoor markets, build your own park sets, community green space

- Where: under highways, abandoned courtyards, underutilized Public Spaces and POPS locations

- When: Permanent (but flexible)

- Why: Relate to new/old rituals, safe interaction if Public Spaces and POPS spaces, sustainable design

- Pandemic: Safe environment and social distancing, comfortable yet safe interaction with Covid-19

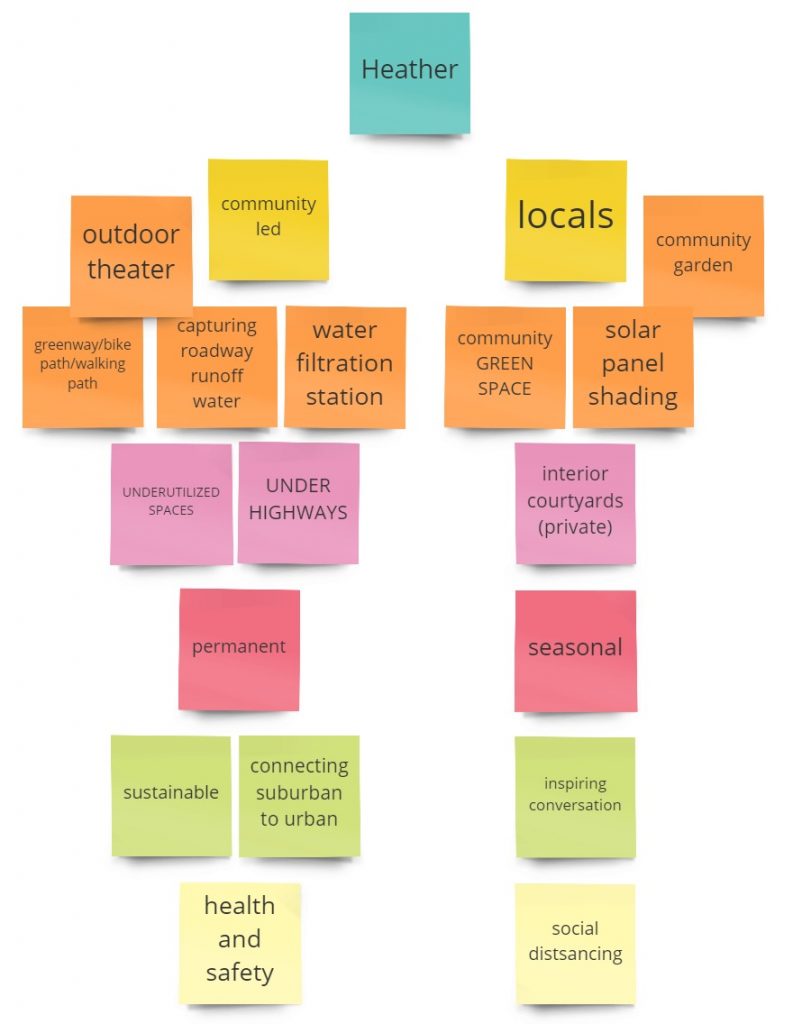

Heather’s Proposal

- Who: locals, community

- What: outdoor theater, greenway, bike trails, paths for walking, capturing roadways runoff water, water filtration stations, community green space, solar panel shading, community garden

- Where: underutilized spaces, under highways, interior private courtyards

- When: Permanent, seasonal

- Why: sustainable, connects suburban to urban, inspires conversation

- Pandemic: a healthy and safe space with social distancing

Image Exchange

About

The Cultural & Geographic Perspective Exchange enables teammates to share different perspectives about a team’s chosen rallying point—a mutual interest, question, or concern. The team’s rallying point will come to life through the multisensory learning embedded in this photographic exchange which gets teammates away from the screen and out into their communities. The photographic essays that you create will help to shed light on your own understanding of the topic and offer insight into the various aspects of the chosen topic within a particular geographic region, city, or culture. While the exchange reveals nuanced views of the mutual topic, as seen from each teammate’s specific cultural perspective, it simultaneously allows for the communication of another, deeper, layer of cultural information. Thus, your view of your topic and each other will broaden. Photographic exchanges stimulate fruitful dialogue about the topic at hand—and a whole new round of cultural questions [1 – p. 151].

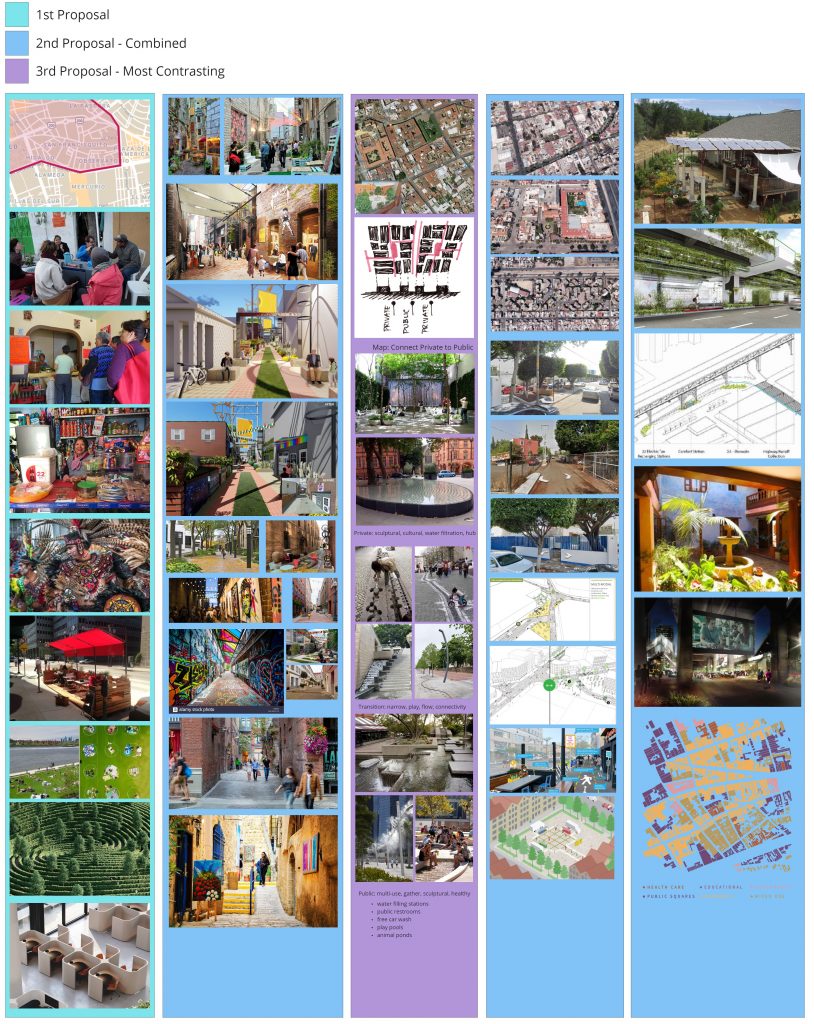

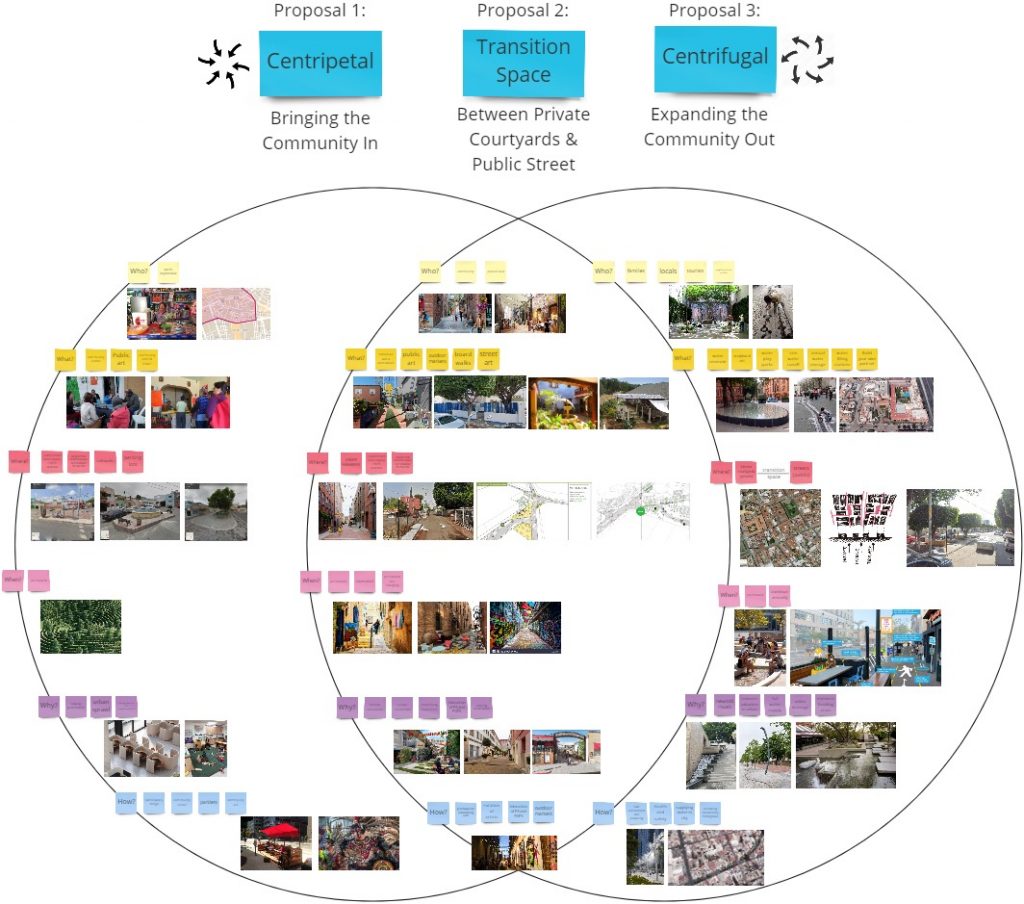

3 Contrasting Proposals

About

We narrowed down the 5 individual proposals into 3 contrasting ones. Proposal 1 is a centripetal urban design method that brings the community in. While, Proposal 3 is the opposite: instead, is a centrifugal urban design method meant to expand the community out. Proposal 2 then is a great in-between urban design method meant to both bring the community in, while expanding out throughout the city.

Datastorming

About

Datastorming is essentially brainstorming with quantitative or qualitative data. Quantitative data is measurable, or numbers-based, which can be appealing to the objective fact-finders on your team. Qualitative data is generally observational, and not numbers-based, which may interest teammates who lean toward more subjective information. This distributed research approach asks each teammate to individually look at an issue through the lens of various secondary sources. Engaging in a Datastorm can add value to a team project in many ways, from both topical and collaborative perspectives. This shared approach to learning new information can pinpoint important details related to a team’s rallying point topic. Based on their data discoveries, teammates then create an information visualization that they can easily share with and use to explain to the rest of the team [1 – p. 161].

Datastorming Breakdown

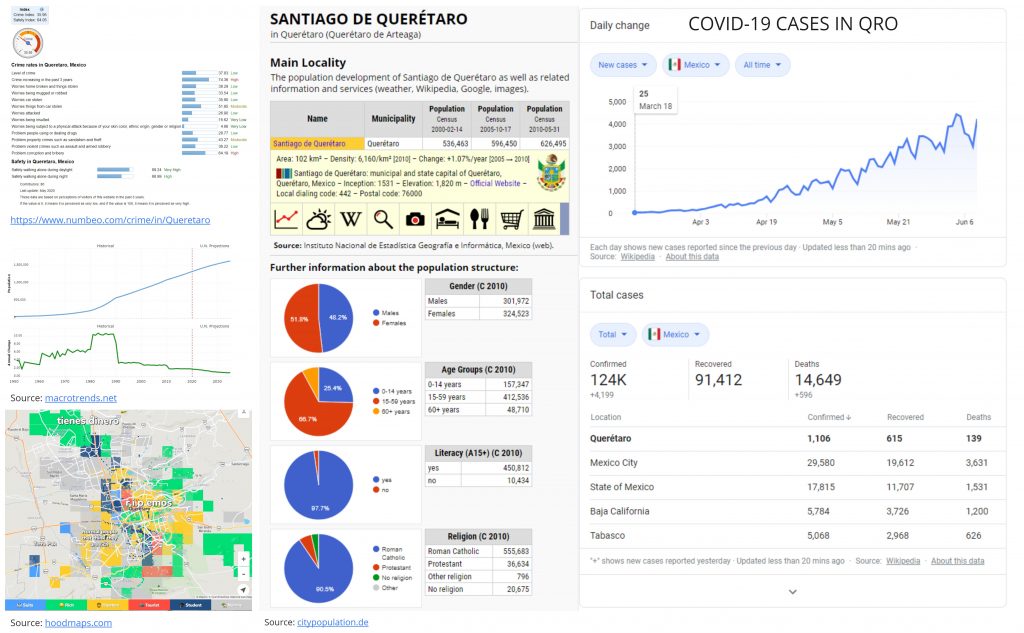

Rachel’s Research – Demographics

Sources

- https://www.worldometers.info/demographics/mexico-demographics/

- https://www.numbeo.com/crime/in/Queretaro

- https://hoodmaps.com/queretaro-neighborhood-map

- https://www.citypopulation.de/php/mexico-queretaroarteaga.php?cityid=220140001

- https://www.macrotrends.net/cities/21863/queretaro/population

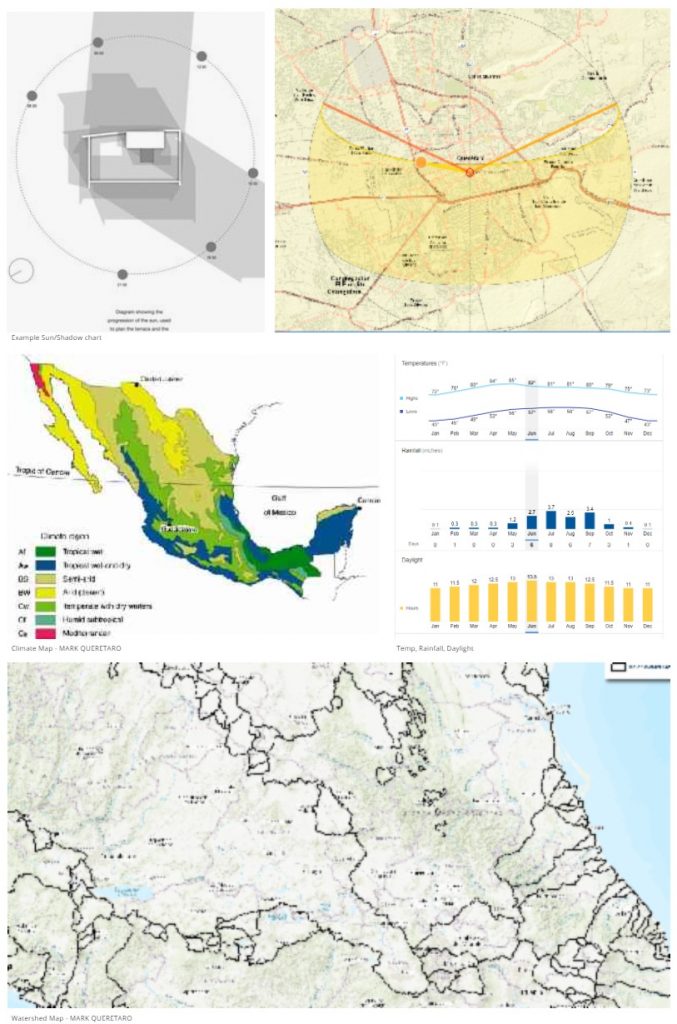

Heather’s Research – Climate & Environment

Notes

- Abstract: Santiago de Querétaro is a UNESCO World Heritage City in central Mexico experiencing exacerbating rates of flooding in its historic center due to increased uphill urbanization overwhelming the aging drainage infrastructure. Historic districts are important economic drivers and shrines of heritage that should be considered when planning for disaster resiliency. This Report explores flood mitigation considerations for historic structures and districts, identifying those best suited for Querétaro and can be implemented at the parcel, district, or public administrative levels [2].

- The area most affecting flooding in the Historic Center is that to the east, the basin of the Querétaro River [2].

- The city continues to expand into the higher areas as official state and municipal policy have discouraged westbound growth, fearing it would lead to the establishment of new residents and tax-paying businesses in nearby Guanajuato State [2].

- Urbanization to the south is of least concern to flooding, as the large Cimatario National Park (See Figure 4-3) serves as a protected green area and watershed divide [2].

- The National Water Commission (CONAGUA) issued a report stating that the flooding was mostly a result of inordinate precipitation and not inadequate infrastructure [2].

Sources

- https://weatherspark.com/y/4986/Average-Weather-in-Santiago-de-Quer%C3%A9taro-Mexico-Year-Round

- https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/bitstream/handle/2152/32192/LULE-HURTADO-MASTERSREPORT-2015.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- https://databasin.org/maps/new#datasets

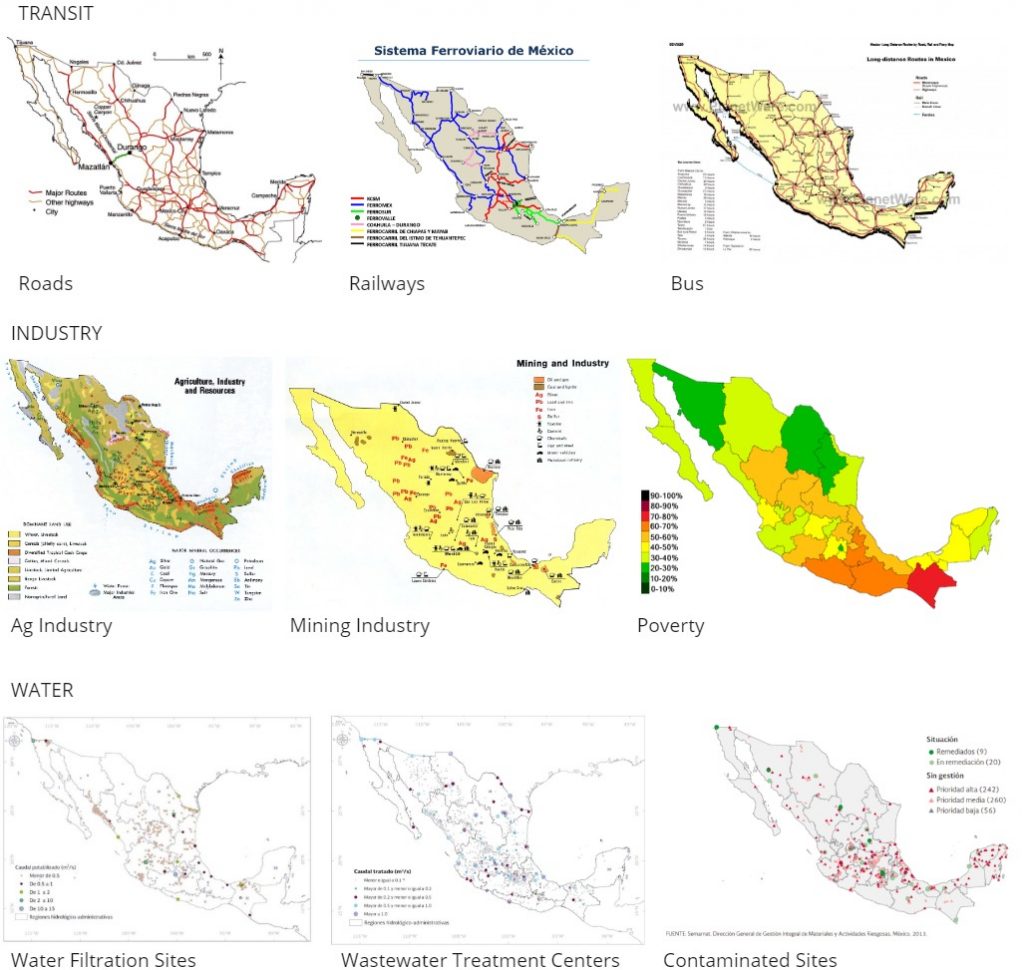

Emma’s Research – Infrastructure

Notes

- Hard infrastructure: built and physical services – (roads, bridges, tunnels, railways, ports and harbors, aqueducts, etc.) [3]

- Soft Infrastructure: fundamental and ideological services – (economic health, social standards, financial systems, education systems, health care systems, government, law enforcement, and emergency care systems, etc [3].

- Mexico’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita in 2008 was $10,235 in a turbulent environment with international financial markets.

- Manufacturing industry represents the largest economic activity in the state of Queretaro [3].

- The industry structure in the state is conformed by micro and small businesses at 95%, and the remaining 1% by large companies, powerful corporations which employ 39% of the labor force working in the industrial sector [3].

- Querétaro’s major cities are home to industrial complexes that produce machinery and other metallic products, chemicals and processed foods. Food processing industries in the state include such well-known companies as Carnation and Purina. The textile industry includes the manufacturing of fabrics from wool, cotton, and henequen (a type of tropical plant). Most manufacturing companies are in or around the capital city. The auto parts company Tremac is one of the biggest employers in Santiago de Querétaro. Handicrafts such as furniture, baskets, pottery, and jewelry are important industries on a smaller scale [3].

- Hydroelectric Power [3]

- Querétaro has a major hydroelectric power plant, Zimapán

- located on Moctezuma River

- Inactive as of 2012

- Drugs and Oil [3]

- The metropolitan area of Monterrey is an important warehousing center for cocaine, marijuana and other illegal drugs bound for U.S. consumers. The natural gas wells and pipelines running through Cadereyta and the U.S-Mexico border have also been the most tapped by thieves, supplying gasoline and other natural resources to Mexico’s criminal underworld.

- 620 mile pipeline from Querétaro to Nuevo Teapa, Veracruz

- Veracruz supplies crude oil

- Thermal-Electric Power [3]

- San Juan del Rio

- Conventional thermal power plant

- Actually owned by Aranica-CPC, not PEMEX or CFE

- Located in San Juan del Rio, Querétaro

- Fuel: Oil

- Capacity: 21 MWe

- Gas Turbine [3]

- El Sauz

- Gas turbine combined cycle power plant

- Owned by CFE

- located in Pedro Escobedo, Querétaro

- Fuel: Natural Gas

- Capacity: 281 MWe

- Water in Agriculture [3]

- 76.6% extraction (63.3 billion cubic meters per year), primarily for irrigation.

- 55% of irrigated lands have had their irrigation systems brought to present-day technical and performance standards.

- 14.5% of water use is for public consumption after farming

- 4% is extracted by the industry for their internal use

- 4.9% percent is used in the course of generation of electricity

Sources

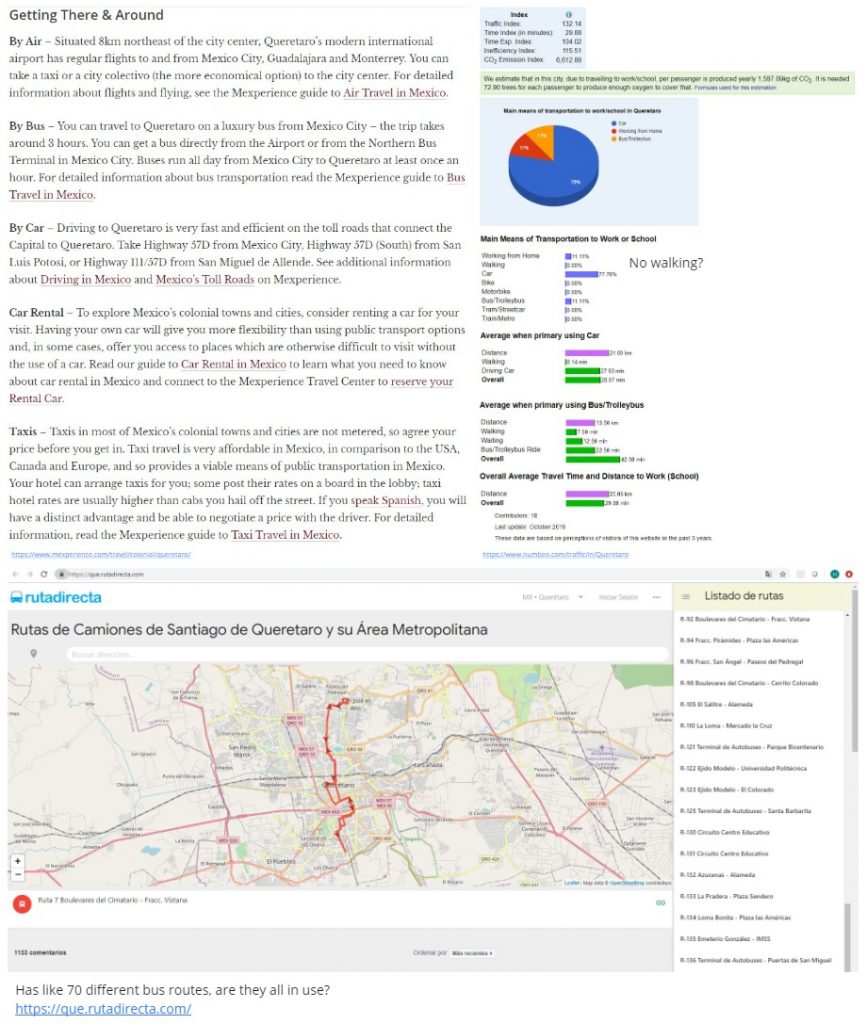

Hunter’s Research – Transportation

Sources

- https://www.mexperience.com/travel/colonial/queretaro/

- https://www.numbeo.com/traffic/in/Queretaro

- https://que.rutadirecta.com/

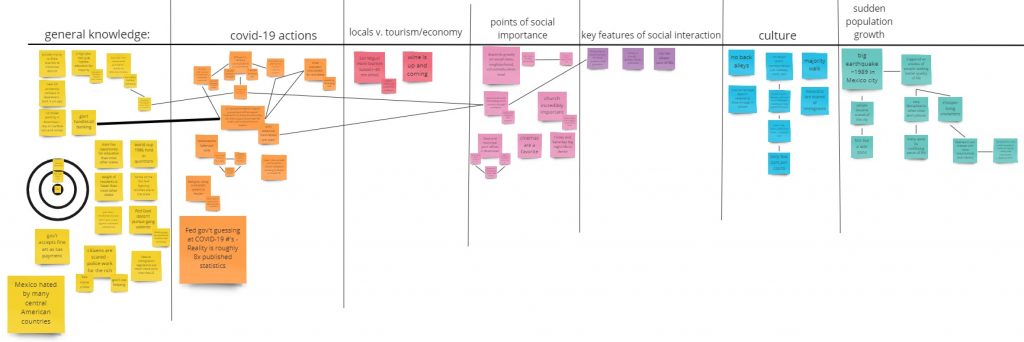

Kristian’s Research – Social Interaction & Culture

Sources

[1] Murdoch-Kitt, Kelly M.. Intercultural Collaboration by Design (p. 145 – ). Taylor and Francis. Kindle Edition.